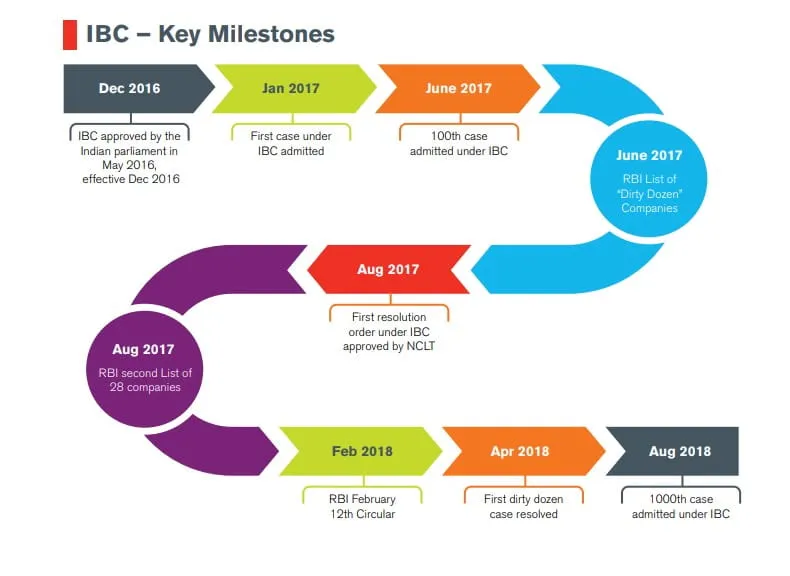

In January 2019, India’s Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code (IBC) completed two years of having been introduced. During this time, it has made an impact like no other regulation or policy. Though only in its infancy, IBC is proving to be more than just another acronym in a series of past failures by Indian regulators to create a viable restructuring mechanism in the country. Since inception, over 1,500 companies have been admitted into the resolution process by end December 2018 and over 1,000 companies have been referred to the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT). While, initially, there were some concerns that the IBC would lack the necessary ammunition, it has proved the sceptics wrong and has been very much a positive for the Indian market. In fact, for the first time, promoters in corporate India are vulnerable and run the risk of losing control over their companies. Further, IBC has created space for a new category of investment -- distressed assets. Post IBC, opportunities for investors and acquirers to take over quality assets at attractive valuations have significantly increased. And, in 2018, it was a major contributor to the overall M&A in India.

The success of IBC can be attributed to some key factors. Firstly and, unlike previously, the IBC has had unanimous support from various stakeholders such as the government, the regulators and the judiciary. Secondly, IBC was able to demonstrate some quick wins highlighting its efficacy and efficiency. Thanks to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), initial resolutions have been focused on large corporate names, which have generated strong global and domestic interest from investors. While only three of the so called ‘dirty dozen’ has been resolved so far, one cannot question the government’s commitment to the process. So far, the results have largely been positive and could ultimately bring significant change to the culture between borrowers and banks in India. It’s indeed a step in the right direction. However, IBC still has a long way to go.

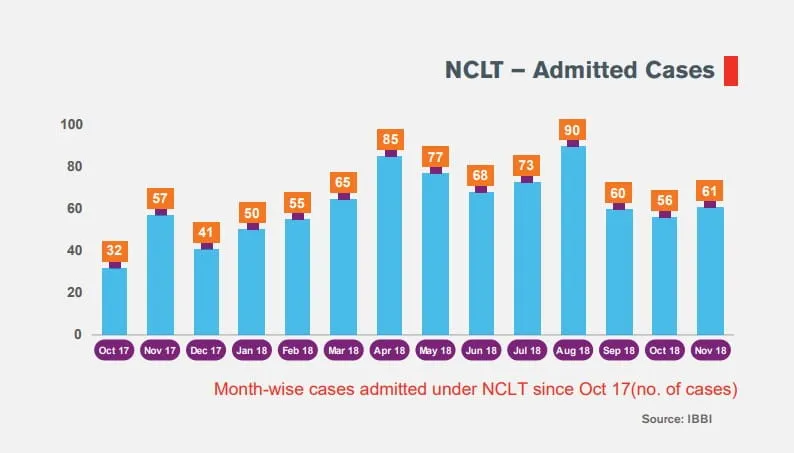

Over the past two years, banks and other creditors are increasingly opting for the IBC route to recover stressed loans. The number of cases admitted has been consistent across months suggesting this was not a onetime assertion. The judicial support toward IBC has also been welcoming. Now there are 12 dedicated NCLT benches for matters related to IBC and more are being introduced. In addition, a new category of professionals, Resolution Professionals (RPs), have been introduced, who are expected to run operations of the company while undergoing the insolvency process under IBC. These RPs also need to be licensed with IBBI, the regulatory for insolvency & bankruptcy.

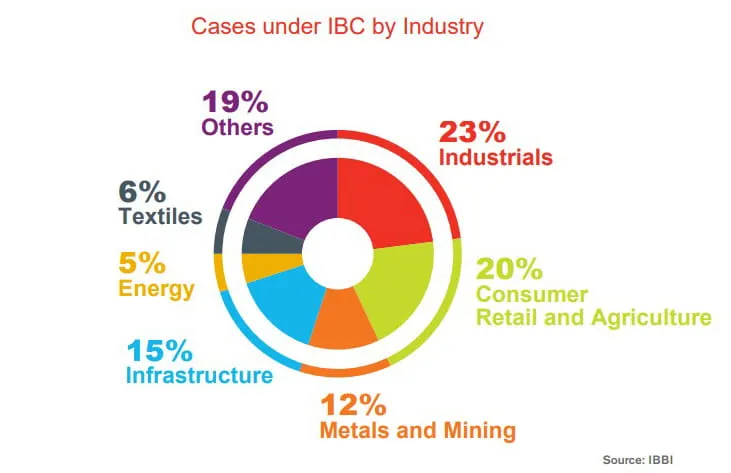

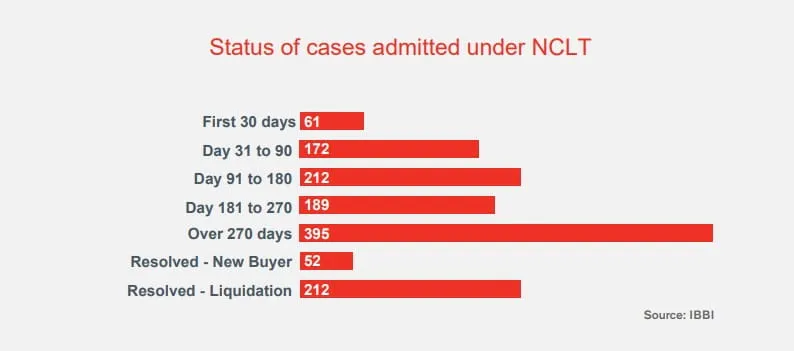

However, the IBC has had its own sets of challenges, especially with respect to the speed of resolution. Of the 1,484 companies admitted under the NCLT, only 79 have achieved closure through resolution and another 302 through liquidation. There is a large pool of companies, which are still seeking resolution. The IBC had also introduced a time-bound approach, with the resolution process to be completed in 180 days, with a grace period of 90 days (total of 270 days). Despite the good intent of the code and introduction of multiple NCLT benches, almost 25 per cent of companies admitted have crossed the 270-day limit, while another 15 per cent companies are between the 181st and 270th day. And, one had expected many cases to be dragged into litigation, especially with promoters losing control, same cases have gone into litigation multiple times and the resolution time for the same has been slow. One expects the current process to gather speed, especially when case laws get built with each incremental resolution and courts gain experience to rely on, while giving judgements. The silver lining though is that the estimated recovery on the resolved cases has been around 50 per cent.

Traditionally, the framework and instruments available for resolution of stressed companies focused inwards with lenders and the company trying to find a solution, which generally meant further extension of loans under new terms and condition. At times, there was equity infusion either by the promoters or a strategic partner but largely the control remained with the original promoters. IBC has hit this very premise, due to which, the concept of insolvency and bankruptcy never really kicked off. Under IBC, the promoters are consciously kept out and not permitted to participate unless they can pay off in full within a pre-specified time. The famous section 29A, which has seen few amendments, restricts the promoters and any related party from participating in the insolvency process. This also provides opportunity for investors to participate without the risk of promoter interference.

Even for investors, introduction of IBC means that the risk of investing in these distressed assets is not much different than those in any other M&A deal. Also, many of the large distressed companies on the block have good underlying assets. The reason they are in distress was that the company or asset may have been over-leveraged, anticipating a demand-supply cycle that didn’t materialise. It is not that the asset itself is necessarily ‘bad’ but rather that certain unfortunate circumstances led the asset into turbulent waters. In such cases, the right investor with the right resources may be able to buy the asset and turn around operations. In 2017 and 2018, distressed M&A values in India have totaled close to $15 billion, a noticeable 12 per cent of total M&A value including some large transactions like Bhushan Steel ($7.4 billion), Reliance Communications ($3.7 billion) and Fortis Healthcare ($1.2 billion). Almost two-thirds of this volume (close to $10bn) has been closed in 2018 alone. Expectations are strong that distressed M&A will be an ongoing theme in the country and will increase as more companies are admitted under the IBC and make their way through the NCLT process.

IBC has brought a culture change in corporate India, but it is a journey which has only just started. Going forward, we see some risks which can impact the efficacy of IBC. Most important is the intent and the commitment of the government to support IBC. The ruling government, due to the majority it enjoys at the center, has been able to introduce certain critical reforms including IBC. India is going through the general elections now and it is important that no matter which party forms the government, it needs to rigorously back IBC. Secondly, the resolution times needs to start coming down. When IBC was introduced, what excited both creditors and prospective investors was the 270-day window for resolution. The initial cases, as expected, are taking much longer than 270 days though still faster than anything in the past. However, increasingly, the success of IBC will rely heavily on ability to achieve closure within stipulated timelines. Otherwise, investors, especially global investors will start losing interest. Lastly, IBC introduced the concept of resolution professionals to bring independence and efficiency. While over 2,000 RPs have registered with IBBI, most of them don’t bring restructuring or insolvency experience. Further, there exist risks of conflict of interests, which are not being taken as seriously at present. A few bad episodes can have a material negative impact on the process and can result in draconian rules.

This article was originally published on Business India.