With protectionism on the rise and countries moving to safeguard their technology and citizens’ data as a matter of national security, companies are incorporating geopolitics into their risk calculations.

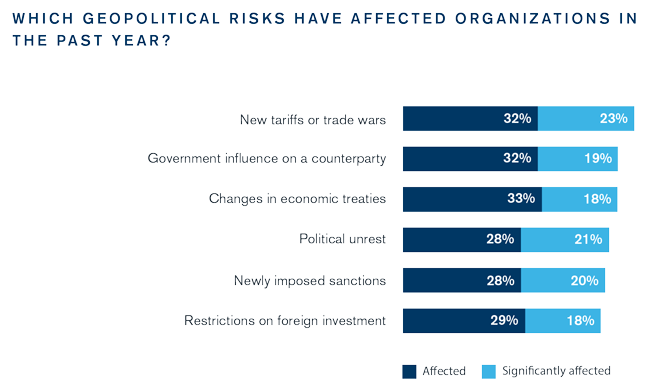

Globalization is often discussed as if it were an irrepressible force of nature or an inevitable consequence of digitalization and a growing consumer class. In fact, globalization is the result of numerous conscious policy choices by countries working individually and collectively to create an environment favorable to free trade. However, the long expansion of globalization has given way to a rise in protectionism: the levying of tariffs, the use of sanctions, the unraveling of established trade alliances, and the expansion of restrictions on foreign investment. Each of these developments has dramatically increased the geopolitical risks that organizations face when doing business abroad. Our survey findings confirm that enterprises are navigating through a growing minefield of regulatory considerations and that they must also anticipate future geopolitical shifts that could disrupt market access, contracts and assumptions underlying their cross-border business strategies.

Moving Beyond Financial Forecasting

Financial forecasting has long been an essential part of strategic planning; entire departments are built around it. Today’s more complex and more dynamic international environment obligates enterprises to expand their geopolitical forecasting capabilities. At first glance, this task may seem daunting, but there are practical steps that companies can take, especially in the due diligence of cross-border transactions.

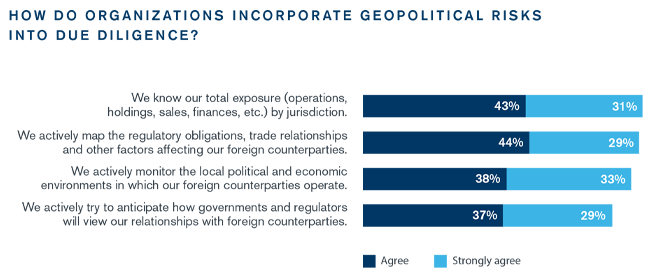

As part of that process, an organization must go beyond assessing its own prospects in a potential cross-border relationship and step back to look at the situation from the counterparty’s perspective. This involves taking the time to understand all the forces—including economic and political ones—to which that counterparty is subjected. Our survey shows that many organizations are factoring these issues into their due diligence.

The extent to which geopolitical due diligence is effective, however, depends on an organization’s sensitivity to forces that may not be readily apparent to foreign observers. Western companies doing business in China, for example, can make the mistake of assuming that a Chinese counterparty with a solid track record of fulfilling its contracts poses little risk of non-performance. However, if the Chinese government later implements a new trade policy that effectively prohibits the company from continuing to fulfill the contract, the company has little recourse in the face of what is essentially a force majeure.

Assessing these risks requires on-the-ground intelligence, starting with a thorough understanding of the counterparty and its context and relationships. Does the counterparty play a role in its regional or national economy that puts it under special scrutiny? To what local regulatory guidelines is it subject? What are the priorities of those regulatory agencies, and how much latitude do they have in establishing new rules? What are the trends in enforcement? Although geopolitical shifts can seem unexpected, governments often signal their intentions prior to making their moves. Mapping the counterparty’s environment in this way allows one to spot the potential ripple effects of future changes in government policy.

Geopolitical concerns can arise in domestic mergers and acquisitions as well. Even if both parties are headquartered in the same country, an acquiring company must thoroughly vet the target’s operations, its value chain, and the business dealings and relationships of the target’s owners and management, including other entities in which they may have an interest. It is quite possible that any of these elements will expand the geopolitical exposure of the acquirer. In the urgency to get the deal done, details such as this cannot be overlooked; doing so can plant the seeds for increased sanctions risk and other problems later.

“National Security” Becomes a Common Refrain

Given the recent overall increase in geopolitical tensions and greater sensitivity to protecting a country’s technology and its citizens’ data, many ripple effects are likely to emanate from the broadening of national security concerns. One vivid example of the expanded role of national security concerns in trade policy involves the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which vets foreign investments in the United States from a national security perspective. (While CFIUS is a high-profile example of a national security regulatory body, many other countries have similar regulatory bodies.) In 2018, the statute authorizing CFIUS was amended; it now instructs the U.S. government to actively work with its allies in aligning foreign investment regulations among countries. Organizations should therefore expect such regulations to play a larger role in global trade. The convergence of anti–money laundering and anti-corruption regulations across jurisdictions illustrates how such an alignment may evolve.

Now more than ever, businesses need to consider national security concerns as a business risk. In performing their due diligence, they should assess national security issues with the same focus that they give to concerns such as antitrust compliance. This entails assessing how a potential business transaction or investment will look from the perspective of the counterparties’ governments, and possibly that of other governments as well. A transaction involving a foreign investor may seem innocuous on the surface, but how regulators choose to categorize a business or its industry, technologies, and data and those of its counterparty can result in heightened scrutiny.

The best response to such scrutiny is to meet it head-on, structuring the deal to mitigate the issues that are likely to raise objections. For example, a U.S. company with a division that has clearance to work with the U.S. Department of Defense might choose to exclude that division from the company’s sale to a foreign buyer. Further, when presenting the deal for CFIUS approval, the company should proactively disclose the potential national security concern, propose mitigating solutions and express its readiness to submit to independent auditing or monitoring to ensure compliance. This level of proactivity requires both a sophisticated understanding of the regulatory environment and a broader view of what constitutes risk.

Now more than ever, businesses need to consider national security concerns as a business risk, including those issues in due diligence just as they do antitrust compliance.

Heightened tensions among nations require that companies sharpen their statecraft—in other words, that they work to understand situations from the perspectives of a broader group of stakeholders, including regulators. Incorporating those points of view into due diligence and ongoing situational intelligence can be an effective way for an organization to deftly navigate geopolitical risk.

Stay Ahead with Kroll

Forensic Investigations and Monitorships

The Kroll Investigations, Diligence and Compliance team consists of experts in forensic investigations and intelligence, delivering actionable data and insights that help clients worldwide make critical decisions and mitigate risk.

Expert Services

Independent expert analysis, testimony, advice and investigations for complex disputes and projects.