As value chains grow and social media creates a web of continual scrutiny, organizations need to know their business partners and customers as never before.

The idea of the organization as a self-contained entity is giving way to the realization that an organization is a single node in a network of relationships—with social media and viral videos putting every element of that network under relentless scrutiny. Third parties have become increasingly central in virtually every sector. Collaboration and partnerships provide the agility and new resources needed for innovation. Globalization has created a wealth of new markets and new suppliers. Social media marketing campaigns rely on “influencers” and “brand ambassadors” to build online followings.

When an enterprise is defined in large part by its relationships, a new level of due diligence is necessary to assess and mitigate the risk of those relationships. Historically, due diligence has centered on legal and financial issues. In recent years, due diligence has expanded to incorporate other issues, such as a potential partner’s ownership structure and cash flows (owing to sanctions) and cybersecurity and data privacy practices (owing to regulations and public expectations). Today, reputational risk is further expanding the concept of due diligence, covering issues such as workplace conditions; social media activity; business practices; and the subject’s own network of customer, supplier and lender relationships.

Due diligence is also becoming bilateral, reflecting the fact that reputational risk flows both ways. A company that sells an asset to a buyer that runs into regulatory problems, maintains substandard working conditions or merely mismanages a once-thriving business can no longer expect those problems to stay exclusively with the buyer; the seller’s reputation may be affected as well.

Our survey found that 79 percent or more of organizations are incorporating reputational factors into their due diligence of candidates for board seats, investors, brand ambassadors and other third parties, depending on the person or entity involved. However, our experience working with clients suggests that organizations vary greatly in their ability to execute a holistic due diligence strategy that is systematic, sustainable and risk-based.

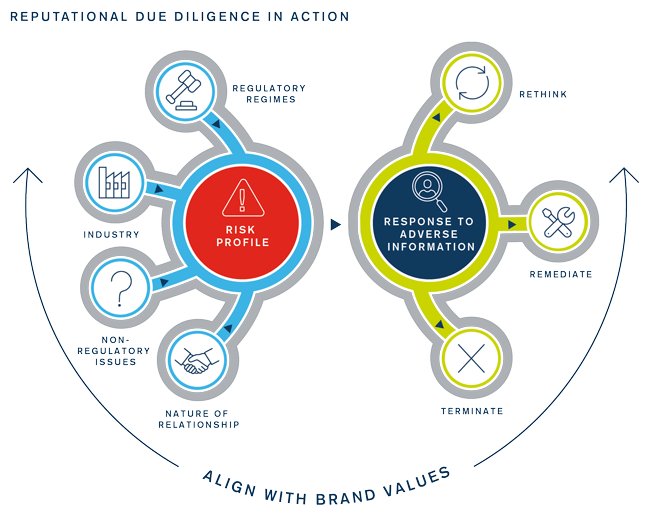

Create the Risk Profile

There is no effective one-size-fits-all approach to due diligence; every relationship brings its own set of potential risks and issues. The first step is thus for the organization to create a risk profile of the party in question. That party’s applicable regulatory regimes provide a starting point. A publicly held company in North America or Western Europe is likely to already be under multiple layers of regulatory scrutiny. In such cases, due diligence is still necessary, but less may be needed because much has already been done by others. At the other end of the risk spectrum, a third party that is privately held in a country with weak anti-corruption enforcement would warrant closer examination.

The industry of the third party is another important element. Certain industries, such as import/export, have relatively high concentrations of illicit activity. Similarly, industries like cryptocurrency and gaming may have still-evolving regulatory structures and thus a greater potential to attract bad actors. Alternatively, a particular industry in a given jurisdiction may have well-developed regulatory regimes but a poor collective track record of enforcement or compliance.

But regulatory compliance is only the start. Given the wide range of non-regulatory standards across jurisdictions for issues such as business practices, working conditions and sustainability, it is entirely possible for a third party to be in compliance with local regulations yet still represent a reputational risk. Indeed, merely identifying which issues to examine can be challenging, requiring a close understanding of the third party’s business. For example, if their products use mica—a ingredient found in everything from cosmetics to metallic paint—they need to be sure that they do not source it from suppliers linked to illegal mining operations using child labor. This is one illustration of the level of holistic thinking required today to stay ahead of a reputational crisis.

Finally, consider the nature of the relationship—the product or service in question, the size of the contract and the level of involvement with the organization’s brand identity. A provider of mission-critical software or a franchisee carrying the company’s name is likely to warrant a deeper level of scrutiny than an office-supply vendor.

While each potential relationship requires its own risk profile based on these factors, certain combinations of risk variables will recur, enabling organizations to create over time a portfolio of risk profile templates that can make the due diligence process more efficient. Such templates remain useful after the onboarding process as rubrics for periodic monitoring of any subsequent changes in the third party’s business or standing.

Map Breadth and Depth

Having established a relationship’s risk profile, one can then determine the breadth and depth of the data collection process so that particular areas of concern can receive more-thorough treatment. Consider the example of an M&A target. It is standard practice to examine the personal and professional histories of management team members. One could also choose to gather similar information on their family members and prior business associates. Similarly, due diligence on a supplier might include examining the due diligence of their own suppliers. Each additional step, however, requires more time and greater commitment of finite resources.

The sheer number of relationships to manage and the amount of information to be gathered about each one make merely collecting the data a significant task. But if due diligence stops here, it is incomplete, with information taken at face value and dots remaining unconnected. A truly holistic approach to due diligence requires depth as well as breadth. For example, does a company that represents itself as a commodities broker have a history that aligns with the number of transactions it purports to conduct? How transparent is the beneficial ownership of the various entities that emerge in an examination of transactions? Digital facades are easy to construct; questions such as these can help expose the structure underneath. But here too, organizations must balance the value of additional information against the expenditure of time and resources.

Whatever the scope of the data collection process, it needs to include a thorough screening of social media posts. It goes without saying that anything objectionable or controversial should raise red flags. But scrutinizing social media activity of a potential executive hire, for example, can also provide significant insight into the person’s values and behavior, which can then be examined for his or her fit with the brand image and corporate culture.

Build a Response Mechanism

Once information has been collected, the exceptions and adverse effects need to be translated into timely and proportionate action. This is not trivial. Consider how often post-crisis investigations uncover red flags that had been ignored. Conversely, a hair-trigger negative response can derail valuable relationships. The guiding principle needs to be the extent to which, when combined with other information, the adverse event—a CEO with a DUI, a facility with safety violations—constitutes a risk indicator sufficient to cause a rethinking of the relationship. Local context is also important, particularly when considering third parties in other jurisdictions. The significance of having a police record, for example, can vary greatly from country to country. But even in cases without cross-border considerations, the data amassed on a subject will vary in its reliability and importance and cannot be taken at face value. Instead, companies need to develop a response mechanism to help them evaluate what they find. As part of that mechanism, it can be useful to assign adverse information to one of three categories:

- Rethink: immediate action not warranted based on the information uncovered, but the issue should be noted and monitored

- Remediate: situations that need to be addressed as a prerequisite for pursuing the relationship

- Terminate: grounds to end the relationship

Even though such categorization is subjective, it provides a framework for acting on due diligence findings.

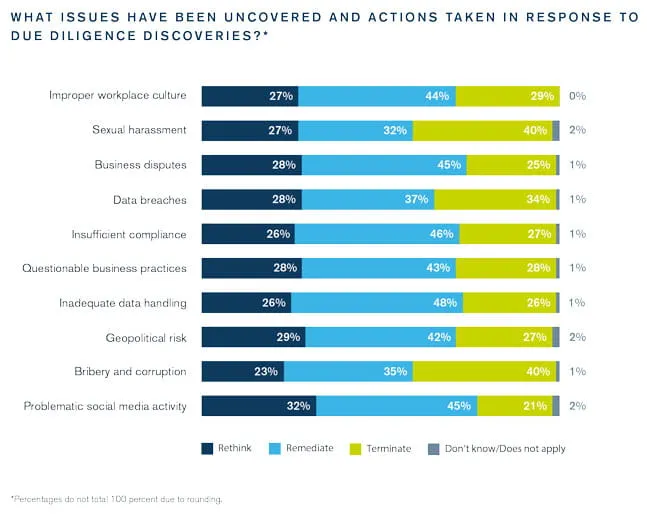

The importance of reputational due diligence can be seen in the frequency with which it uncovers issues that fall into one of the above categories (see Figure 1).

Align With Brand Values

Historically, the main drivers for due diligence have been transactions and compliance requirements, leading some people to view due diligence as a housekeeping task. However, the always-on hyper-network of traditional and social media, combined with rising public expectations for corporate citizenship, has greatly increased the importance of reputational issues. Because due diligence plays a critical role in mitigating that risk, the due diligence process must reflect the organization’s brand values. Enterprises with high profiles in corporate social responsibility, for example, will want to pay extra attention to those issues. Global consumer brands should ensure that their extensive supply and distribution chains reflect their messaging as much as their marketing and advertising do.

In an environment of greater scrutiny, higher risk and more unknowns, due diligence requires more effort than it once did. However, that effort can reap rewards that render due diligence not just a necessary task but also an important differentiator and strategic asset.