This article was contributed by Andrea Boltho, Duff & Phelps Real Estate Advisory Group (REAG) Advisory Board Member and Emeritus Fellow, Magdalen College, University of Oxford

The April 2017 note titled "The World Economy is growing" concluded that the world economy was growing steadily if not spectacularly and that this growth was likely to continue, subject, however, to one major risk, at least in Europe. This risk was political: populist parties seemed to be gaining strength by promoting a nationalistic, Eurosceptic and at times protectionist platform. Over the last few months this risk has clearly diminished. In France, the right-wing National Front was soundly defeated in both the Presidential and Legislative elections and in Italy the populist 5 Star Movement, somewhat unexpectedly, lost a good deal of ground in several important local elections. Even the recent British Parliamentary vote was interpreted by many as a setback for the “hard Brexit” option favored by the more nationalist wing of the Conservative party. Though future political shocks cannot be excluded, the economic climate, which was already looking up, seems to have improved further.

The surge in optimism shown by numerous confidence indicators in Europe at present may also have been given a boost by the pragmatic bank settlements reached in Spain and Italy. While the shareholders of Banco Popular, of Banco Popolare di Vicenza and of Veneto Banca were wiped out, most commentators felt that the slate had been cleaned and that bank lending to business might strengthen from now on in both countries. It was really only in Germany that outrage was expressed because the Italian deal, in particular, by using state aid, sidestepped the EU’s rules and undermined the nascent banking union.

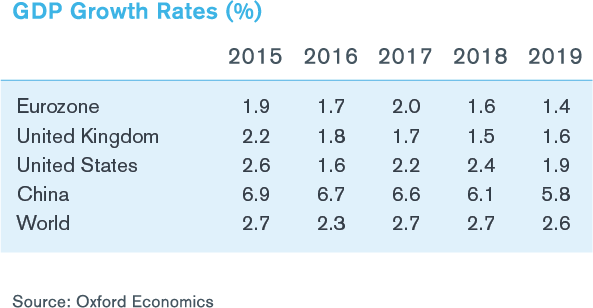

The biggest changes in the outlook concern the United States, whose growth prospects now look distinctly weaker than they did not so long ago. The hope that the US economy would expand by 2½ to 3 per cent next year was premised on significant tax cuts and large infrastructure spending. Neither of these two policies look as if they will be implemented any time soon. Congress is still bogged down in its attempts to reform so-called “Obamacare” and will have to find a, possibly contentious, agreement to lift a ceiling on total Federal debt by the Autumn. In addition, the president and Congress are far from having reached a common position on tax reform. Under the circumstances, the chances of launching a vast program of tax cuts and investment in infrastructure in the near future have dwindled, as have the prospects of significantly faster growth.

In Europe, on the other hand, recent data all point to somewhat stronger activity in the coming year. German confidence, in particular, is at record high levels. This is promising since rapid growth in Germany has a powerfully favorable impact on the rest of Western Europe. Confidence has also risen quite strongly in France aided, no doubt, by a “Macron effect”. Spain is still steaming ahead and even Italy is showing encouraging signs of a pick-up in activity despite continuing household pessimism. A welcome development, which has by now continued for over a year, has been the decline in European unemployment. For the Euro area, for instance, the unemployment rate in May this year was barely above 9 per cent of the labor force, as opposed to an over 10 per cent rate a year ago, and back to levels not seen since 2009.

The present recovery on the Continent has been strongly helped by the virtual end of fiscal austerity in most countries, by the continuing very permissive monetary policy stance of the European Central Bank (ECB) and by the weakness of the euro’s exchange rate. Fiscal austerity is unlikely to make a come-back over the next few years. Monetary policy, on the other hand, will almost certainly tighten over that time horizon, but, according to the ECB, such a tightening will be both gradual and modest. The euro has, rather unexpectedly strengthened against the dollar in the recent past, but its level is still rather competitive as compared to what it was only a couple of years ago. All in all, therefore, the policy environment looks like it's being relatively accommodating. The same should also be broadly true for the United Kingdom, even if monetary tightening (because of relatively high inflation) may come quicker there than on the Continent.

The biggest external risks to this favorable outlook come from China and the United States. In China the authorities, worried by the rapid rise in company debt, are gradually tightening monetary policy. Hopefully, this will avert a potential financial crisis and result in only a modest deceleration in growth. A sharper slowdown, however, cannot be excluded and this would have significant negative effects on Europe. The danger coming from America is a shift towards protectionism and the ensuing retaliation that would no doubt come from countries targeted by Trump. Trade wars can be very costly.

Within Europe the main risk is of renewed tensions within the Euro area. The Greek saga is still going on and anti-Euro populism, more subdued at present, could nonetheless return (in Italy for instance), and threaten the single currency. More broadly, intra-EU conflicts are likely to continue, due to disputes over fiscal policy, security issues or over immigration (with Italy strongly opposed to the restrictive stance of some East European countries). It is unlikely that a possible Macron-Merkel axis will be able to stem many of the centrifugal forces that are present inside Europe.