The COVID-19 emergency is clearly not over. The recent outbreak of the Omicron variant is casting a long shadow over the world economic outlook. As yet, there is uncertainty as to how lethal the new variant is. Early reports suggest it may be less virulent than its Delta predecessor, but in the face of a tsunami of new cases, many countries have tightened restrictions and imposed partial or localized lockdowns. More may follow as winter pressures on health systems increase.

This is bound to affect economic activity. As it is, the pace of expansion was decelerating from the rapid tempo experienced in much of 2021. Renewed restrictions on mobility, let alone lockdowns, can only slow it down further. They could, in particular, reinforce two negative effects that were mentioned in the October note: supply shortages and rising inflationary pressures. A feature of previous lockdowns was sharp swings in demand away from services towards goods. Soaring demand for durables and other goods could not be fully met by supply, thus generating both bottlenecks and rising prices. There is a clear danger that both these outcomes could be repeated on this occasion.

As it is, inflation has risen rapidly in recent months. The latest figures show rates not seen for many years: nearly 7% in the U.S., some 5% in Western Europe (of the major economies, only Japan seems immune as of now). Many observers and policy makers have argued that this is a transitory phenomenon, and there is, no doubt, some truth in this. The continuation of bottlenecks and a possible change in inflationary expectations could, however, lead to more persistent price pressures. Wage settlements, so far, have remained moderate almost everywhere and this provides some comfort, but should labour shortages become more widespread, wage pressures could also increase.

Monetary policy is beginning to respond. The Bank of England raised interest rates in mid-December, the Federal Reserve System is planning to reduce bond purchases in the near future and has signaled that as many as three interest rate increases could take place in 2022. Even the dovish European Central Bank has decided on a reduction in bond purchases under its special pandemic program. Interest rates have also risen in Norway and in several emerging countries (but have fallen in Turkey). Rates remain very low in the advanced countries but there has been some upward creep in longer-term bond yields. In early December, these were negative in several European countries. By early January, this remained true (and then only marginally) in Germany and Switzerland.

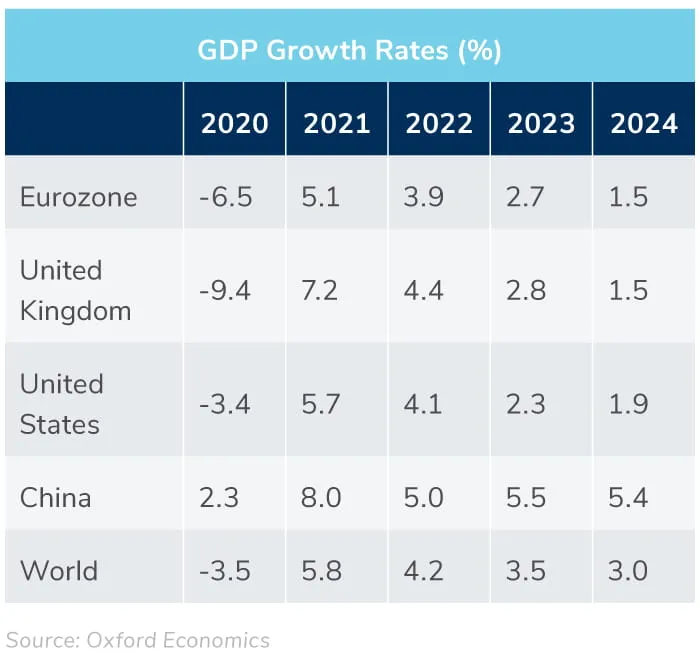

Higher interest rates and lower consumer demand, as inflation erodes purchasing power, together with declining household and business confidence, all suggest that 2022 will begin in a subdued fashion. Confidence could also be affected by the military tension between Russia and Ukraine. A fully-fledged Russian invasion seems unlikely, but energy prices in Western Europe could rise even further. As a result, growth forecasts have, inevitably, been trimmed. The U.S. economy should remain relatively buoyant, helped by large fiscal injections (even if the Build Back Better plan is not approved by the Senate). Western Europe is likely to slow down quite sharply from the 2021 tempo. Germany, which was most affected by supply bottlenecks last year, could see some growth acceleration. Britain, France and Italy, on the other hand, will be growing more slowly than in 2021. All these forecasts, however, are more uncertain than usual in view of the unknowns surrounding the spread of the Omicron variant.

China has so far managed to avoid the worst effects of the pandemic with deaths from COVID-19 kept to a minimum thanks to early draconian controls. As a result, growth slowed down sharply in 2020, but rebounded strongly last year. There are, however, two clouds on the horizon. The first relates to the real estate sector. Several major construction companies are in difficulty and the largest one (Evergrande) is technically bankrupt. The authorities have sufficient instruments in their hands to prevent a major financial crisis, but a sharp slowdown in activity seems inevitable. Given that the construction sector has been one of the major, if not the major, engine of growth in recent years, the economy’s overall expansion will be muted. The second cloud is the Omicron variant itself. Its incidence in China has, so far, been limited but given its infectiousness, it has already led to the imposition of some severe localized lockdowns and more may follow. Inevitably, this would further restrain activity.

Prospects for other emerging countries are almost certainly even less buoyant. Three threats are faced by the developing world: rising U.S. interest rates, a slower growing Chinese economy and the pandemic itself. The first threatens countries with large current account deficits and dollar-denominated debts; the second, large commodity exporters, the third, almost all emerging economies given their very low rates of vaccination. Some of the major vulnerable countries are Argentina, Brazil, Egypt and Turkey. Eastern Europe is in a stronger position (it is less indebted, and its exports are mainly manufactures), but, by the standards of Western Europe at least, it also suffers from a relatively low vaccination count.

The real estate sector continues to show impressive strength in many of the advanced economies. Real house prices were still surging at the end of 2021 raising fears of overheating, according to the European Central Bank. Increases have been particularly pronounced in the U.S., the UK, Germany and Scandinavia. All these are countries or areas that have seen the largest increases in teleworking and hence a greater demand for space outside the major urban conurbations. Savings accumulated during the pandemic, continuing low interest rates and a renewed eagerness on the part of banks to extend mortgages have also helped. It remains to be seen how sustainable this trend will be. On the one hand, the spread of the Omicron variant could strengthen it further; on the other, rising interest rates could well lead to a correction. Outside housing, while the office, hospitality and retail sectors are still suffering, demand has risen sharply for laboratories and data centres. Space in life science or medical equipment labs is at a particular premium, especially in locations close to universities and research institutions.

By Professor Andrea Boltho, Duff & Phelps Real Estate Advisory Group, A Kroll Business, Advisory Board Member, Emeritus Fellow, Magdalen College, University of Oxford.