Economic recovery is continuing across the world even if its rhythm has somewhat slowed down, particularly in the U.S. but also in China. Old uncertainties have not gone away and new ones have appeared. This suggests that there could be some further cooling from the pace experienced in the recent past. First and foremost is, of course, the continuing threat posed by COVID-19 (as was already underlined in the July note). New cases and deaths are still being recorded everywhere. Numbers are lower than they were during the last wave (more so in Europe than in the U.S.), but winter is approaching, raising fears of a new wave. The so-called Delta variant is still virulent and new, potentially dangerous, variants could emerge. All this slows down the recovery and dents confidence.

In addition, confidence is also being affected by two further unfavorable economic developments: continuing supply bottlenecks in some crucial areas and rising inflationary pressures. Freight rates for both dry cargo and container ships are soaring. Additionally, shortages are being recorded for semi-conductors, and a number of other materials and spare parts as well as for some commodities, and especially natural gas. Gas prices have more than doubled over the last six months because of surging demand, low stocks, port congestions, and possibly, Russian hesitancy in supplying to Western Europe. These various shortages and bottlenecks are slowing down production and pushing inflation upwards to rates not seen for years (3% or more in Europe and 5% in the U.S.). The forecasting consensus argues that much of this surge in prices reflects a simple rebound from the depressed price levels of 2020. There is, no doubt, some truth to this but, for the time being at least, prices are still rising. For inflation to become endemic, it would have to affect expectations of future inflation, and therefore, wage claims. Settlements, so far, have been modest, despite reported shortages of workers in particular sectors (e.g., road haulage and hospitality), but some wage acceleration cannot be ruled out.

Economic policy seems to be following a “wait and see” posture. Fiscal policy is still expansionary in the U.S. and could become more so even if only a reduced version of Biden’s fiscal plans receives Congressional approval. In Europe, on the other hand, some countries are beginning to worry about rising public debt levels, and modest retrenchment may start in the near future. Disbursements from the EU’s Next Generation Fund could, however, more than offset this, especially in Southern Europe. Monetary policy remains permissive everywhere. The scale of quantitative easing will be reduced in both America and Europe in the coming quarters, but interest rate increases are, as yet, improbable. The only factor that could change this picture would be a further and sustained rise in inflation.

Not all is doom and gloom, however. Forward-looking indicators still point to a continuing recovery; labor markets show high levels of vacancies as well as robust employment growth, and most forecasts still see a return to 2019 levels of output in the advanced countries by the middle or the end of next year. The U.S. remains at the head of the pack, but several European countries (in particular, the UK, Spain and Italy) are also staging rapid recoveries.

The picture in the emerging world is patchier. Chinese growth is still relatively rapid but bumpier, with production cutbacks imposed by some local authorities to meet emission targets. In addition, there have been energy shortages as well as financial difficulties. The Shanghai stock market’s capitalization fell by nearly one trillion dollars following a campaign designed to reign in excessive monopoly power in high-tech firms while mounting corporate indebtedness, especially, but not exclusively, in the Evergrande company, is hitting the real estate sector. The authorities, however, retain sufficient firing power to prevent a full-fledged financial crisis. Elsewhere, activity is, if anything, strengthening in several East European countries and Turkey, but faltering in many others, partly because of pandemic effects and partly because of (as in the advanced countries) supply chain disruptions, chronic port congestion and widespread shortages. And the emerging world outside China remains fragile in any case, in view of the limited progress that mass vaccinations have made so far.

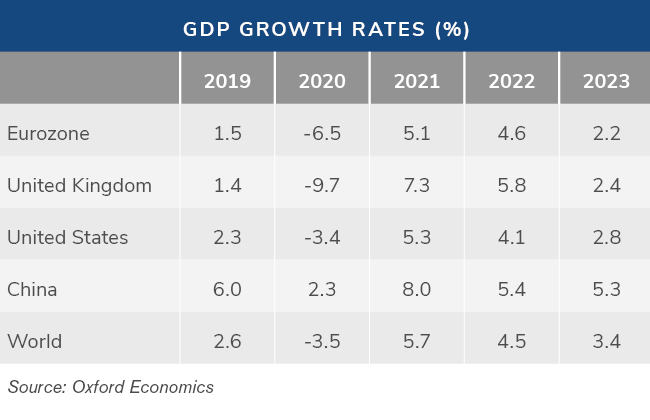

A further divergence between the emerging and the advanced world can be found in the real estate sector. The growth of house prices in the developing world has remained subdued, while it has soared in the developed world. The latter phenomenon has defied expectations. Traditionally, when recessions struck, house prices would decline. In the Eurozone, for instance, during the financial recession, GDP declined by over 4% between 2007 and 2009 and real house prices by nearly 7%. In the U.S., the comparable figures were close to -3% and as much as -20% (in the UK -4.5% and -18%). On this occasion, despite a Eurozone GDP decline of 6.5% in 2020, real house prices rose by 5% and by a further 5% in the first half of 2021 (the divergences in the U.S. between these two variables are equally pronounced).

The most plausible explanations for this almost unprecedented phenomenon come from the record low levels of interest rates, the resilience in personal incomes, thanks to the various fiscal policy measures designed to protect household income and employment from the recession and changing demand patterns in favor of larger dwellings and suburban locations. These have been encouraged by the move towards more work from home, in turn, induced by the pandemic. Linked to the pandemic is also a concomitant rise in the price of warehouses. Online retailers require more space than traditional shops because a greater variety of goods is expected by buyers. The e-commerce boom of the last two years has thus raised the demand for additional space, boosting the value (and the rents) of storage facilities.

By Professor Andrea Boltho, Duff & Phelps Real Estate Advisory Group, A Kroll Business, Advisory Board Member, Emeritus Fellow, Magdalen College, University of Oxford.

Connect With Us

Stay Ahead with Kroll

Real Estate Advisory Group

Leading provider of real estate valuation and consulting for investments and transactions.

Valuation Services

When companies require an objective and independent assessment of value, they look to Kroll.