Globally, fine amounts have edged up following a massive fall from the peak of the big benchmark manipulation cases in 2013 and 2014. This in large is dominated by U.S. enforcement actions.

Of the large fines globally included in the scope of this research, fines against firms increased from US$19.7 billion in 2015 to US$25.9 billion last year. For the first six months of 2018, meanwhile, the total was US$8 billion.

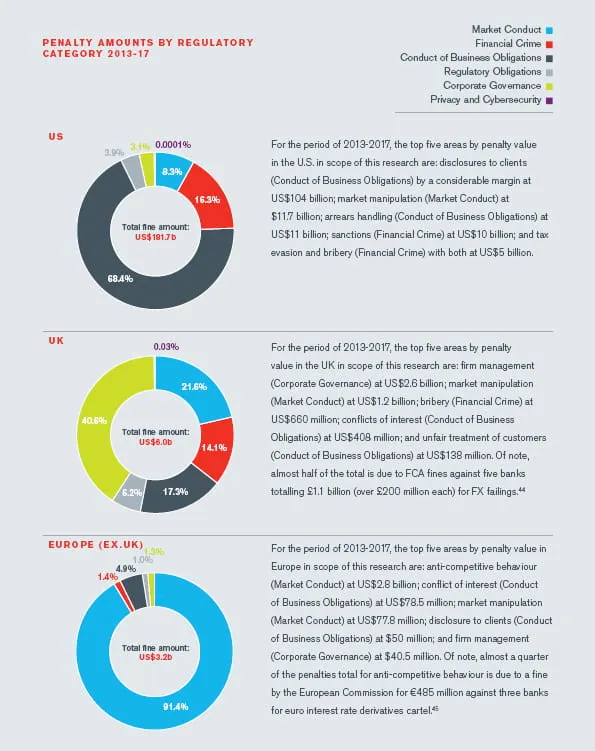

That, though, obscures a more complex picture. First, the overall figure is heavily influenced by activity of the U.S. regulators. In 2017, the U.S. accounted for US$24.4 billion of the total, an even higher proportion than usual. Moreover, this figure is itself skewed by some large fines in bribery cases against non-financial firms; AML and fraud cases against financial services firms; and other fines relating back to the financial crisis cases. Even more significantly, two extremely large fines (relating to disclosure and client communications) together account for half the 2017 U.S. total.

Less expensive...

In fact, the overall trend seems to be towards less reliance on fines in financial services. In the UK, for instance, total fine amounts are down from a peak of £1.5 billion in 2014 and £958.4 million in 2015 to £865.2 million in 2017; this 2017 figure is, however, largely skewed by a £510 million penalty issued by the Serious Fraud Office to a non-financial firm in relation to corruption, false accounting and failure to prevent bribery.1

That is not to say the traffic is all one way. There’s evidence, for instance, that China is ramping up enforcement action and fines (although published data is difficult to come by). It is also interesting that in the area of AML – regularly in the top five categories for fines – regulators without much of a track record for issuing fines have become more active. We see this particularly with the French PSRA and the Central Bank of Ireland, for example.

We see no sign yet of a return to the peak penalty levels seen earlier in the decade. Those huge fines also largely reflected the size of the organizations involved; big banks get fined big amounts and small firms are fined smaller amounts.

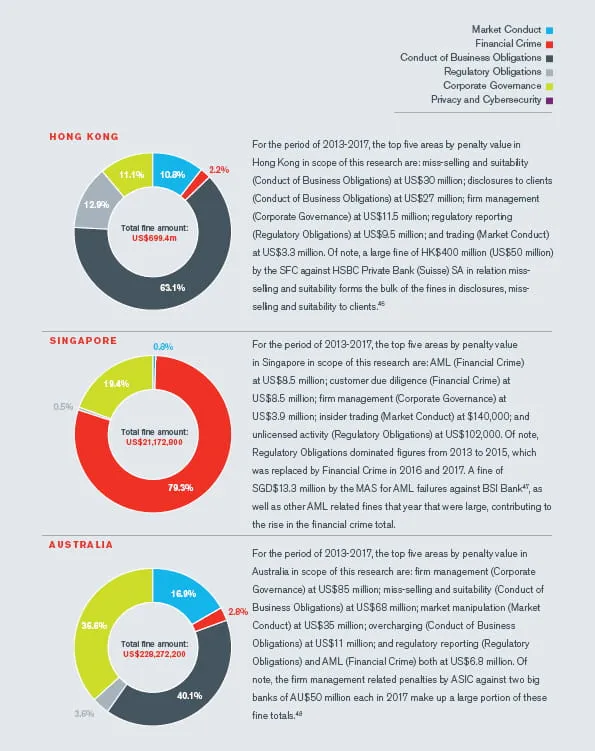

Despite the drive from regulators to promote individual accountability, there is a similar declining trend globally in the fine amounts against individuals from 2016 to 2017, and this trend looks set to continue for 2018. When we look at individual jurisdictions, however, these vary widely, with the U.S., Europe (excluding the UK) and Hong Kong having increased fine amounts; this is despite, except for Europe, a decline in number of fines.

But change is coming

Arguably, the pattern of declining fines against firms is also evidence of two other trends. The first is some disillusionment on the part of regulators with the efficacy of fines on firms to alter behavior – at least when applied on their own. Following the discovery of the benchmark manipulation cases, regulators tested almost to destruction the theory that very high penalties would result in cultural change within financial services firms affected. The evidence that they do is, at best, mixed.

Regulators are therefore questioning the effectiveness of large fines and are coming up with new ways to tackle abuses, including a greater emphasis on restitution and disgorgements (see Nick Bayley’s article: Making good: New thinking on compensation for public market investors).

That is not to say we will not continue to see significant numbers of penalties imposed against firms – and large fines for the worst failures and biggest businesses. It does, however, mean that regulators, particularly in the most established financial centers, may be less solely reliant on them in future. Instead, we could see the employment of a more sophisticated approach, in which a range of sanctions targeted at firms, are used in conjunction with an increased emphasis on individuals.

The second trend is related to this: Billion-dollar fines have simply lost their power to shock, not just in the industry but also among the public. Like the regulators, the public too have perhaps been left wondering if the firms affected really feel the impact. That does not mean that they want to see abuses go unpunished. It just means they are no longer impressed with big fines that only hurt the shareholders. Instead, they want to see individuals held to account. With the introduction of accountability regimes across the globe, it may only be a matter of time before the number of fines and the profile of cases against individuals rival those made against firms.

Sources

1 https://www.sfo.gov.uk/cases/rolls-royce-plc/